C-130.net: Tell our readers a bit about yourself and an overview of your military career?

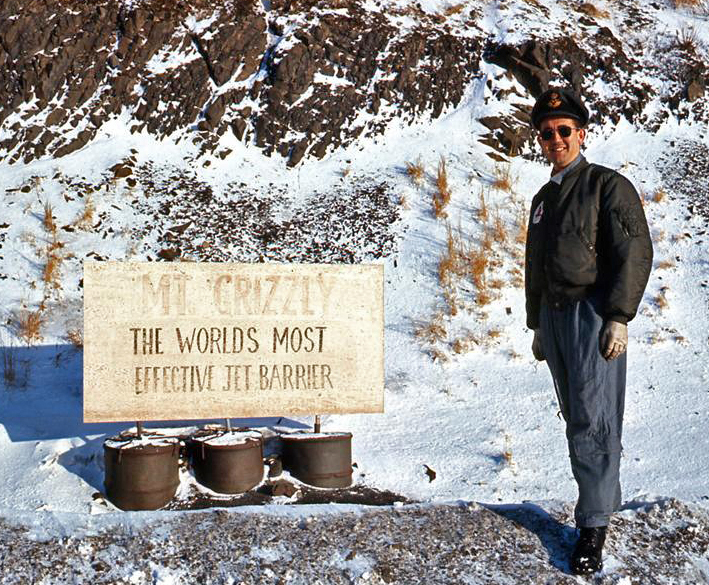

Charles: I joined the RAF straight from school and began training as a pilot. Basic training on the Piston Provost was followed by Advanced training on Vampire jets, and I was awarded my "Wings" in August 1958. My first tour was on the meteorological squadron in Northern Ireland flying Hastings aircraft, and then followed a transfer to Transport Command and further tours on Hastings, primarily in the tactical role (formation flying, dropping paras and various stores etc), but also with flights around Europe and to bases in the Far East. In 1965 I was posted on to a strategic squadron flying the Comet 4c and spent the next 18 months flying RAF personnel to and from our bases in the Near and Far East, as well as occasional VIP flights to the USA. In 1966 the RAF began to re-equip its tactical squadrons with the C-130K and I took the opportunity to return to the tactical world. However, soon after joining my RAF Hercules squadron I was selected to go on exchange with the USAF and was assigned to fly with the 17th TAS/TCS "Firebirds" in Elmendorf, Alaska, flying the C-130D-6 and C-130D (the ski-bird). Conversion training on the C-130A was carried out at Ellington AFB, Texas, followed by the tactical training phase at Lockbourne AFB, Ohio, before I finally arrived in Alaska in August 1968. I flew with the 17th until August 1970 before returning to the UK and commencing a stint as a flight commander at an RAF Apprentice School. This ground tour was happily cut short after 18 months when I was promoted to Squadron Leader and was posted to the Belfast squadron as Flight Commander Ops, eventually leaving the RAF in 1975.

C-130.net: Was exchange common during that time period? Why was the exchange with a squadron that was not like any RAF C-130 unit?

Charles: The RAF had, and probably still has, a well developed exchange scheme with a number of Commonwealth and foreign air forces around the world, but by far the biggest was with the USAF. In the late 60s I believe there were up to 90 RAF personnel in the States of various ranks and specialities. The pilot exchanges were much sought after so I can count myself as one of the lucky ones. If I remember correctly, there were two C-130 exchanges even before the RAF equipped with the C-130K: there was one at Sewart AFB and initially one at Dyess AFB, Texas. This latter one transferred to Elmendorf in the mid 60s. As far as I know, I had two predecessors on the 17th and three who followed.

C-130.net: What training goes into flying the C-130D ski model?

Charles: Training for the new pilot on the 17th was thorough and comprehensive. As well as a spell under supervision to acclimatise with flying in Alaska, there were also a number of fields into which a check ride was mandatory before being able to fly in as A/C. Then followed introduction to operating on the Greenland ice-cap, under the supervision of an IP. Ground instruction was quickly followed by flying up to the two radar sites, carrying out approach and landing procedures, open snow landings, and take-off technique including the use of JATO. At the end of the training came the check-ride! Even having qualified, it was usual to operate on the ice-cap at least once more as a co-pilot, such were the conditions often experienced.

C-130.net: What was the biggest risk when flying the C-130D ski model? What was a typical mission?

Charles: The 17th was equipped with six C-130D-6 aircraft and six C-130D skibirds, and its primary role was to provide tactical and logistic support for US forces in Alaska and the Aleutian islands. Additionally, two ski-birds and crews were based at Sondrestrom AFB, each crew being rotated on a two-week basis. Each week a "rotator" aircraft would fly in from Elmendorf and change one of the crews. The two radar sites on the ice-cap, Dye2 (7650' amsl) and Dye 3 (8700amsl), were re-supplied on an as-required basis most of the year. This changed during the POL re-supply phase, when an additional plane and crew arrived and flying became very intensive. The aircraft each had a 3300 gal fuel tank installed in the hold and from these the underground diesel tanks at the sites were replenished to "FULL", with the aircraft engines still running. POL took place each year in late spring, lasted up to three weeks and during this time close on 600000 gals of diesel were delivered to the two sites.

Each site had an ice-way which had metal impregnated flags running either side of its length. In IMC conditions the usual procedure was to overfly the site at 1000' and then fly a rectangular pattern to finals. The nav picked up the flags on his radar and in effect gave a step-down radar approach to landing or go- around. Once on finals, wings had to be held level with directional changes made with the rudder. In the event of VMC, a visual positioning to final was optional and if conditions warranted it an open snow landing could be carried out.

The biggest risk factors involved in ice-cap ops with the ski-bird were undoubtedly the often hazardous weather conditions, with rapidly changing conditions, temperatures often -50C or below, strong winds, the rugged nature of the terrain and almost constant white-out conditions. Operating at such high altitudes also had adverse effect on engine performance. On the technical side, the main hazard faced was a malfunction of the nose ski, which if not resolved meant return to Sondrestrom and a snow/foam strip laid to run the nose ski along. Thankfully, this was not a common experience.

C-130.net: What differences did you notice between the RAF and the USAF?

Charles: Generally, RAF and USAF squadrons work and operate in a similar way, so it was not too difficult to fit in with the different culture. There were the usual differences in the use of the English language and some differences in technical terms, example tech log/ Form 700, gear/ undercarriage, go-around/overshoot, but the biggest difference was in the composition of squadron personnel. Due to the sometimes hazardous nature of the flying task of the 17th, all members were very experienced, all the pilots when I joined were A/C qualified, most were Majors with some Captains and nearly everyone had had recent service in Vietnam. By the end of my tour co-pilots began to be posted in the squadron. My RAF tactical squadrons would comprise typically of company grade officers (Flight Lieutenant/ Flying Officer), three field grade officers as flight commanders, with the CO as a Wing Commander (Lt/Col). One other difference I remember was that all flights in the USAF were authorised by having "Orders" cut, while the RAF authorised flights in the Authorisation Book, signed off by one of the execs.

C-130.net: Do you have a call sign? If so, what is it and how did you get it? Did you get a different one during the exchange?

Charles: This may have changed, but in my time RAF pilots didn't have individual callsigns. However, while operating on the ice-cap out of Sondrestrom it was usual for the pilots to pick a call sign for themselves. Among others there was a Red Baron, a Blue Max and a Snoopy. My call sign was "Redcoat '76" which I thought was appropriate in the circumstances!

C-130.net: Any stories that you would like to share?

Charles: It would be remiss of me, while recounting my times on the 17th to not mention the rather inglorious start to my tour. Fairly soon after my arrival in Alaska, I flew over to Greenland to be checked out on ski operations on the ice-cap. After a number of flights out to the radar sites I set out on my check ride. The visit to Dye 3 went without incident and from there we headed for Dye2. The weather was marginal, with poor visibility, blowing snow, strong winds and the ice way declared closed as it needed dragging. The pattern was begun, with the intention of carrying out an open snow landing when visual. The ARA went as planned but on touchdown the left gear/ski landed in a deep hole in the snow. The gear became detached and on its rearward travel damaged the left para door and the left tailplane. The wing down attitude led to the No 1 propeller striking the snow, which in turn led to serious engine damage and a fire, which was quickly put out. The crew were rescued by the snowcat and spent the night at the site (ie in the bar) before being picked up the next day by another skibird. Very embarrassing but happily nobody was injured. The engineering team flown in from Elmendorf did a fantastic job in extreme weather conditions in repairing the aircraft sufficiently for it to be recovered to Sondrestrom; once there, further work was carried out and the plane was subsequently ferried gear down (and chained) to IRAN in Birmingham, Alabama . C-130D 0-70492 was eventually fully restored and returned to Elmendorf.

C-130.net: What was a common activity during down time in Alaska?

Charles: Alaska was an outdoor paradise and most squadron members took full advantage of the many pursuits available. Some owned campers, while others owned 4 wheel drive trucks, or skidoos or canoes. Hunting was popular for some. But what almost everyone possessed was fishing gear, as fishing for salmon, trout and grayling was fantastic. Fishing tackle accompanied many of us on most internal Alaska flights during the season, in order to cast a line where applicable while the aircraft was being loaded. It also was a must on our detachments to Sondrestrom. There were also two fish camps, one near the town of Seward, the other at King Salmon AFB, which were for the exclusive use of military personnel. Two ski areas were located in the combined Elmendorf/ Ft. Richardson base area. My wife, myself and our two sons (then aged 6 and 4) quickly took up fishing, learnt to ski and really enjoyed the outdoor life. The boys also taught themselves to ice skate on a rink which was built by the residents behind our quarters.

C-130.net: Any other experiences?

Charles: Lasting memories of my tour in Alaska/Greenland:- » Hand flying on the Greenland ice-cap in VMC,out to the Dye sites and the low level recoveries to Sondrestrom.

- » Flying re-supply missions out to Fletcher's Ice Island (T3), an iceberg near the North Pole, working out of Point Barrow.

- » Successfully locating, on an unscheduled SAR mission, a missing light aeroplane and its pilot, which had crashed near Narsarsuaq. The pilot was later ferried to Sondrestrom where his survival was suitably celebrated.

- » Friday nights in the Sondy "O Club"!

- » Engine failure on take-off at Cape Romanzov with a 2 Star General sat on the flight deck.

- » Bleed- air duct overheat and fire on take-off after IRAN at Birmingham, Alabama.

- » Completing Arctic Survival School in Fairbanks, Alaska.

- » Two week -long visits to the USAF Staff college at Maxwell AFB in 1969 and 1970 to join in seminars on defence topics and to exchange ideas and hospitality with USAF officers on the staff course.

C-130.net: Favorite squadron and why?

Charles: It has been a difficult decision to make but I think my tour in the RAF flying Belfast aircraft out of Brize Norton was the most enjoyable. There were a number of reasons for this. First of all there was the euphoria of an unexpected promotion, followed by the belief that I had been given one of the best postings in the transport force as the Flight Commander (Ops). The Belfast, (similar to the C-133) only equipped 53 Sqn and was much maligned because of early weight and drag problems and the fact that it had been somewhat overtaken by the jet age. It was underpowered because the proposed larger turbo-prop engine under development was cancelled. Though manual controls made it difficult to fly, it had an excellent flight system and autopilot and when used correctly in the medium range heavy/bulk cargo role was almost indispensable to the RAF. The squadron only had one regular scheduled flight, a weekly run to Cyprus via Malta. All other flight were "Specials". This meant interesting and often challenging flights to most parts of the globe, but especially to the Far East, Canada, the Caribbean and the USA. With the last, I was able to input some of the experience gained during my time on the C-130 with operations in North America, which was very satisfying. Due to its unique status as sole Belfast operator, the squadron was given a fair amount of autonomy in its operating methods. All of the above added up to a thoroughly enjoyable final tour in the RAF.

And finally. I left the RAF in 1975 and joined Britannia Airways, a charter airline owned by Thomson Holidays. Initially I flew the Boeing 737 on routes around Europe and North Africa. Eventually 767s and 757s joined the fleet and the routes expanded to include the USA, Caribbean and holiday spots in the Far East and Australia. I finally retired in 1997 having flown a total of 17000 hours, which included 1150 on all marks of the C -130. In my 41 years as a pilot, I certainly count my time on exchange with the USAF flying the D and D-6 model as some of the most exciting, enjoyable and rewarding moments of my career.

Thanks to Squadron Leader Charles G Furlong RAF - Retired (17th TAS/TCS 1968-70) who was interviewed by Jonathan Somerville in 2013.Note: Errors and omissions in the above text can be added here. Please note: your comments will be displayed immediately on this page.

If you wish to send a private comment to the webmasters, please use the Contact Us link.